| Journal of Current Surgery, ISSN 1927-1298 print, 1927-1301 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Curr Surg and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.currentsurgery.org |

Original Article

Volume 6, Number 2, June 2016, pages 52-56

The Pigtail Catheter for Pleural Drainage: A Less Invasive Alternative to Tube Thoracostomy

Asmita A. Mehtaa, b, Amit Satish Guptaa, Aziz Kallikunnel Sayed Mohameda

aDepartment of Pulmonary Medicine, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Ponekara, Kochi-682041, Kerala, India

bCorresponding Author: Asmita Mehta, Department of Pulmonary Medicine, Amrita Institute of Medical Sciences, Ponekkara, Kochi, Kerala, India

Manuscript accepted for publication June 24, 2016

Short title: Pigtail as an Alternative to Chest Drain

doi: http://dx.doi.org/10.14740/jcs300e

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: Thoracostomy tubes are a mainstay of treatment for removing fluid or air from the pleural space. Placement of a chest tube is, however, an invasive procedure with potential morbidity. In an effort to reduce these complications, the use of percutaneous pigtail catheters in place of traditional large-bore tubes for thoracostomy and pleural drainage has been described. The aim of the study was to determine the role of pigtail catheters in adult population for drainage of pleural effusion.

Methods: It was an observational study. All consecutive patients with pleural effusion requiring drainage were subjected to either tube thoracostomy or pig tail drainage. A standardized questionnaire was prepared for retrieving data. Outcomes of interest were time to drain and total duration of hospital stay.

Results: A total of 92 patients (71 men and 21 women; age range, 17 - 86 years; mean age, 54 ± 15 years) were enrolled into the study. Thirty-five patients were treated with traditional chest tubes, whereas 57 patients were treated with pigtail catheters. There were no significant differences in either drainage days or hospitalization days between the chest tube group and pigtail catheter group (9.81 ± 6 vs. 9 ± 5.6 and 13.8 ± 6 vs. 13 ± 5.7, respectively).

Conclusions: The pigtail catheter offers reliable treatment of effusions and is a safe and less invasive alternative to tube thoracostomy. There was no significant difference in time to drain and duration of hospital stay in both the groups.

Keywords: Pleural effusion; Tube thoracostomy; Pigtail catheter; Complications

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Pleura is divided into two layers, a parietal layer which lines the inner aspect of the chest wall and a visceral layer which covers the lung and lines the inter-lobar fissures [1]. Tube thoracostomy is a valuable tool for the treatment of various pathologic conditions of the pleural space. Recent literature suggests that treatment with small caliber tube thoracostomy is equally effective and less painful than treatment with large caliber tube thoracostomy in the treatment of pleural infection [1-3]. Additionally, it has been shown that wire-guided chest tube placement allows for more accurate positioning when compared with the classic surgical technique [4]. Placement of a chest tube is, however, an invasive procedure with potential morbidity. Complications include hemothorax, perforation of intrathoracic organs, diaphragmatic laceration, empyema, pulmonary edema, and Horner’s syndrome [5, 6]. In an effort to reduce these complications, the use of percutaneous pigtail catheters in place of traditional large-bore tubes for thoracostomy and pleural drainage has been studied in very few studies [5-8]. The present study was planned to see the benefit of pigtail drainage over conventional tube thoracostomy for draining pleural fluid.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

It was a prospective observational study and was conducted at a tertiary care academic institute in department of pulmonary medicine. Study period was April 2012 to April 2013. Informed consent was obtained from the patients for participation in the study. The study was approved by institute research committee.

Study subjects

Inclusion criteria

All consecutive patients above age of 18 years with diagnosis of pleural effusion requiring drainage were screened for the study.

Exclusion criteria

Post-traumatic effusion and iatrogenic effusion were excluded.

A detailed history and thorough clinical examination was done for all included patients. A standardized questionnaire was prepared to retrieve patient details. Complete blood count, renal function test, liver function test, prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time and other relevant investigations were done. Chest radiograph was taken before and after the procedure as and when needed. Patients requiring drainage were subjected to either tube thoracostomy or pigtail catheter drainage as per discretion of treating physician. All procedures were done at bedside. Ultrasound guidance was used as and when necessary.

Intervention

Intercostal drainage (ICD) was inserted as per BTS guidelines for insertion of ICD [9].

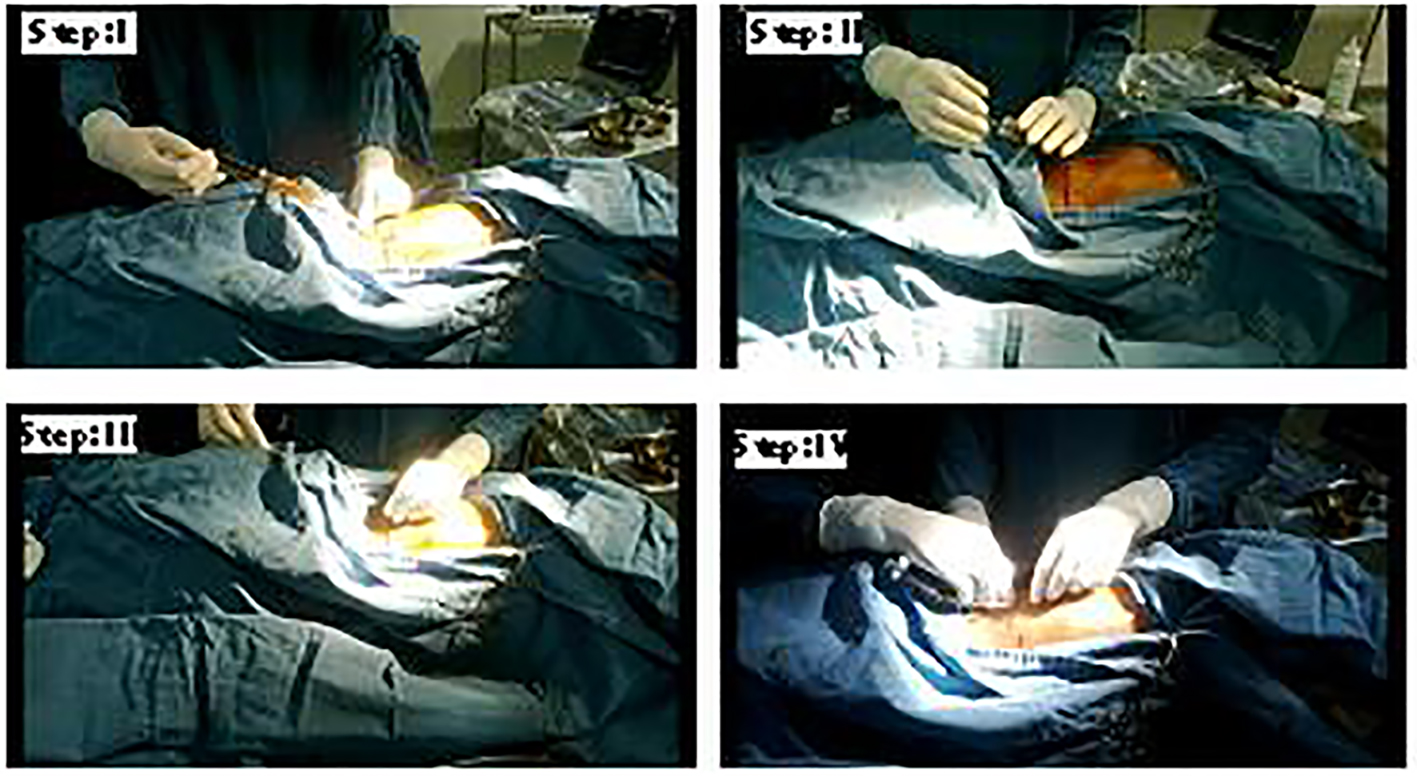

Modified Seldinger technique [10] was used for pigtail insertion (Fig. 1). The details of the procedure are as follows. A needle insertion is made just above the top of the lower rib to avoid injury to the intercostal neurovascular bundle. Few milliliter of pleural fluid is withdrawn to confirm that the distal end of the needle is well inside the pleural cavity. Then the guide wire is passed into the pleural space through the needle. A dilator is used thereafter to create adequate tract. A pigtail is inserted in such a way that the side holes are well inside the pleural cavity. The pigtail is then attached to standard thoracic drainage system.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Steps of modified Seldinger technique. |

Beside pigtail catheter and ICD insertion, standard therapy as per etiology of the effusion was given to all the patients. For tuberculous pleural effusion, anti-TB drugs as per WHO guidelines were given [11]. For parapneumonic effusions, antibiotics were given as per the IDSA recommendations [12]. Intrapleural instillation of streptokinase (dose 2.5 lac units q12 hrly up to six doses) was done for loculated pleural effusion if required [13]. Malignant pleural effusion patients were subjected to talc or betadine pleurodesis prior to removal of tube or pigtail [14]. Bedside ultrasound guidance was used for all the patients as and when required [7].

Primary and secondary endpoints of the study were defined as below.

Primary end points

1) Time required for complete clearance (from time of insertion to complete radiological resolution + 24-hour drain < 50 mL); 2) Duration of hospital stay (day of admission to day of discharge); 3) Success (clearance of opacity in CXR without need for repeat intervention/surgery).

Secondary end points

1) Intolerable pain following the procedure (pain score > 5 on Universal Pain Assessment scale) [15]; 2) Patient mobility after the procedure (good/average/poor).

Statistical analysis

Descriptive data were presented as mean ± SD (range). The relationship between type of drain and duration of hospital stay as well as time to clear and pain scoring and patient mobility after drain were tested using a Chi-squared test in the univariate analysis. P value < 0.05 was taken as statistically significant.

| Results | ▴Top |

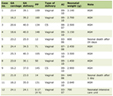

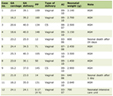

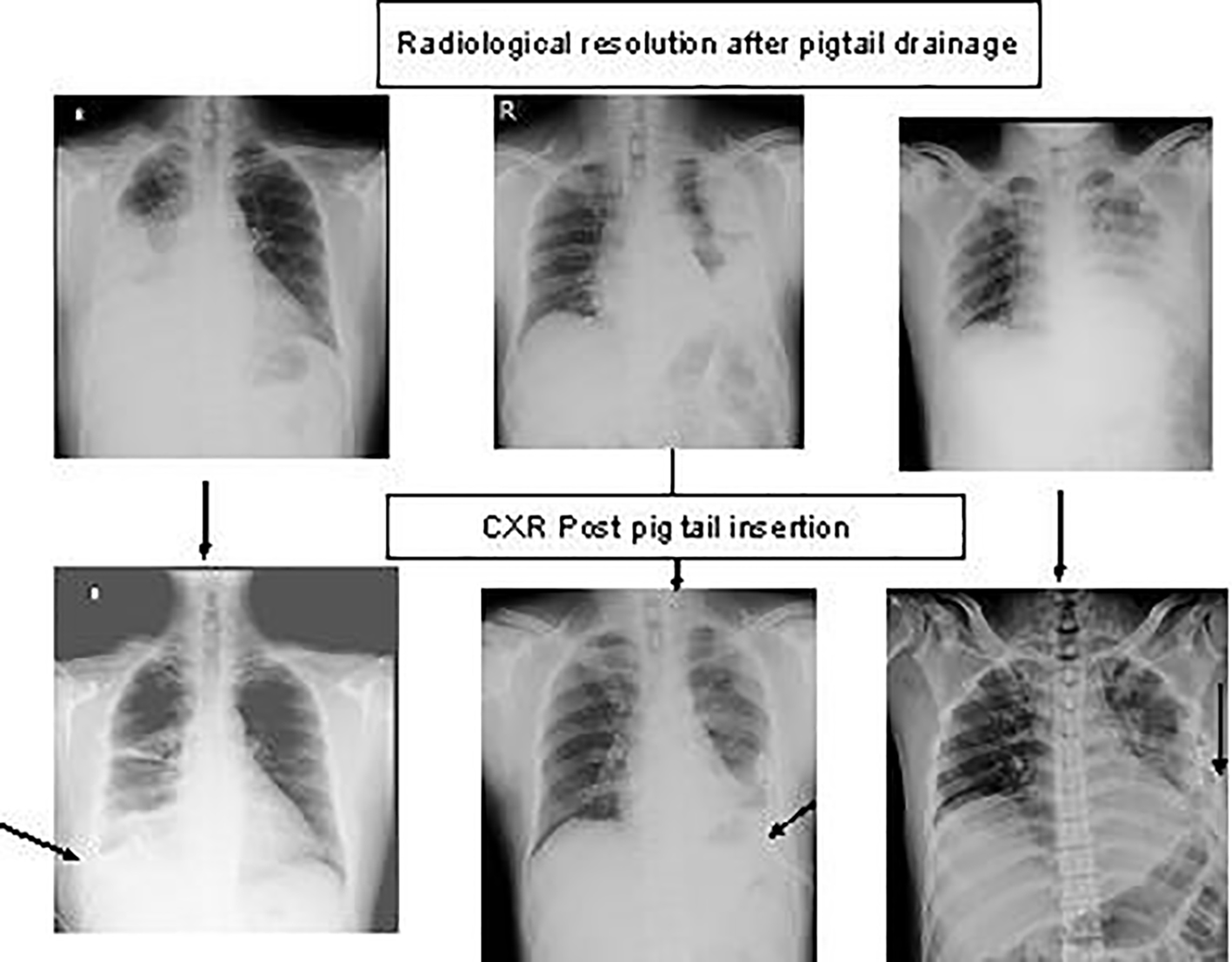

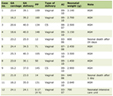

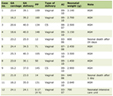

A total of 92 patients were included in the study. There were 57 (61.9%) patients in pigtail group and 35 (31.8%) in ICD group. Baseline demographics of both groups are depicted in Table 1. The mean age and gender percentage were equal in both groups. Pneumonia was the commonest cause of effusion followed by tuberculosis (TB) and malignancy in both groups. The duration of drainage of pleural fluid using pigtail catheter ranged between 3 and 30 days with a mean of 9.81 ± 6.4 days, whereas it was 9 ± 5.6 days for ICD. Primary and secondary points of the study observations are shown in Table 2. There was no statistically significant difference found between two groups when compared for time to clearance and duration of hospital stay. P value was < 0.001 for pain scores and mobility following the procedure when pigtail group was compared with ICD. Success rate for pigtail was 94.7% and ICD was 85.7%. Radiological images of patients prior to and following clearance are shown in Figure 2.

Click to view | Table 1. Baseline Demographics of the Study Cohort |

Click to view | Table 2. Primary and Secondary End Points |

Click for large image | Figure 2. Radiological imaging of the patients before and after pigtail insertion. |

Subgroup analysis was done and time to clearance as well as duration of hospital stay was measured for different groups as per different etiologies as shown in Table 3.

Click to view | Table 3. Subgroup Analysis |

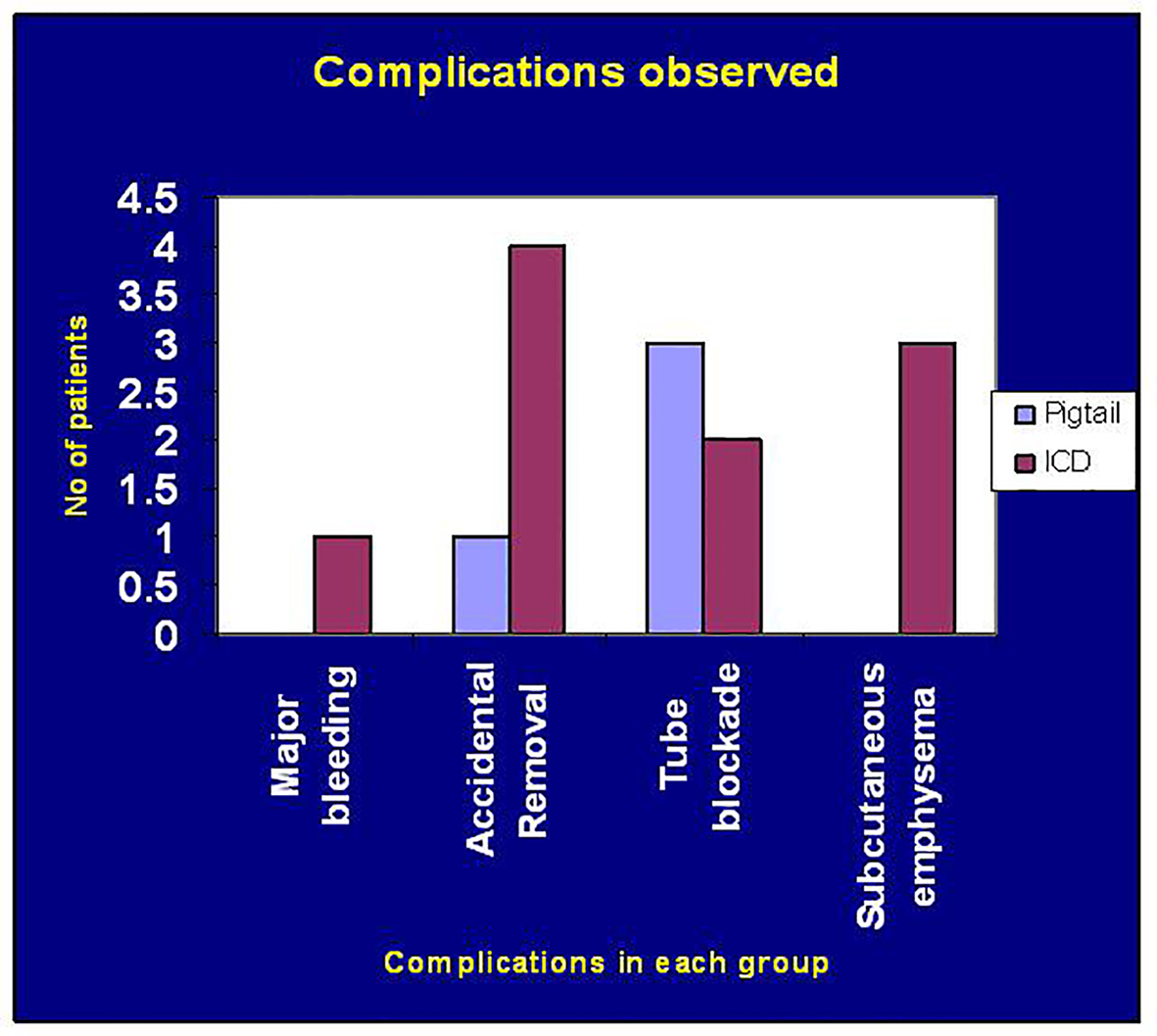

Complications of pigtail catheter included pain and blockage of the catheter, whereas subcutaneous emphysema and accidental removal requiring re-insertion was noted in patients with ICD (Fig. 3).

Click for large image | Figure 3. Chart showing post-procedure complications observed. |

| Discussion | ▴Top |

Wide bore chest tubes are conventionally used for drainage of fluid or air from pleural cavity. However, traditional large-bore chest tubes, placed by either blunt dissection or by trocar assistance, may have significant morbidity. Small-bore chest tubes have become more popular recently because of their effectiveness in a variety of pleural diseases [1-5]. The British Thoracic Society now recommends small-bore chest tubes (10 - 14 F) for pneumothoraces, parapneumonic effusions, and malignant effusions [17]. We compared effectiveness of ICD with pigtail catheter in present study. Pneumonia related effusion was the commonest cause in both groups followed by malignancy and TB. We found that there was no statistically significant difference in duration of hospital stay and time taken for clearance in both the groups. Sixty-one percent patients in pigtail group had loculated effusion. Still success rate was higher in pigtail group (94.7%) when compared with ICD group (85.7%). There were no major complication in either group but accidental removal was more common in ICD group. Pigtail catheter caused less pain and allowed good mobility compared to ICD.

We did comparison of our study with previously published Indian and international study. The comparison is shown in Table 4 [7, 17, 18]. It shows that total duration of hospital stay was higher in present study when compared with another Indian study while time to drain was almost similar in all the groups. The success rate in present study was matching with study by Jain et al, but was higher when compared with studies done in China and Egypt.

Click to view | Table 4. Comparison of Present Study With Other Published Studies |

The present study had some limitations. It was an observational study conducted in a tertiary care referral center and may not represent the general population. The study was not randomized and the decision to put pigtail or ICD was solely based on treating clinician’s description. It may have led to selection bias. Even though, standard of care given to the patients other than ICD and pigtail was similar in both the groups, blinding was not possible considering the nature of the study. The study size was small and large multicenter studies are required to extrapolate the results.

Conclusion

Pigtail catheters are a safe and effective method for drainage of pleural effusion. Time to clearance and total duration of hospital stay were similar in both groups. Pigtail was better tolerated with respect to pain and mobility post procedure. It should be considered as the initial draining method for a variety of pleural diseases in affording patients.

Conflicts of Interest

None.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of the paper: Mehta AA. Data collection and analysis: Gupta AS, Aziz KS, and Mehta AA. Writing of the paper: Mehta AA.

| References | ▴Top |

- Gotsman I, Fridlender Z, Meirovitz A, Dratva D, Muszkat M. The evaluation of pleural effusions in patients with heart failure. Am J Med. 2001;111(5):375-378.

doi - Rahman NM, Maskell NA, Davies CW, Hedley EL, Nunn AJ, Gleeson FV, Davies RJ. The relationship between chest tube size and clinical outcome in pleural infection. Chest. 2010;137(3):536-543.

doi pubmed - Rivera L, O'Reilly EB, Sise MJ, Norton VC, Sise CB, Sack DI, Swanson SM, et al. Small catheter tube thoracostomy: effective in managing chest trauma in stable patients. J Trauma. 2009;66(2):393-399.

doi pubmed - Munnell ER. Thoracic drainage. Ann Thorac Surg. 1997;63(5):1497-1502.

doi - Gammie JS, Banks MC, Fuhrman CR, Pham SM, Griffith BP, Keenan RJ, Luketich JD. The pigtail catheter for pleural drainage: a less invasive alternative to tube thoracostomy. JSLS. 1999;3(1):57-61.

pubmed - Tsai WK, Chen W, Lee JC, Cheng WE, Chen CH, Hsu WH, Shih CM. Pigtail catheters vs large-bore chest tubes for management of secondary spontaneous pneumothoraces in adults. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(7):795-800.

doi pubmed - Liu YH, Lin YC, Liang SJ, Tu CY, Chen CH, Chen HJ, Chen W, et al. Ultrasound-guided pigtail catheters for drainage of various pleural diseases. Am J Emerg Med. 2010;28(8):915-921.

doi pubmed - Roberts JS, Bratton SL, Brogan TV. Efficacy and complications of percutaneous pigtail catheters for thoracostomy in pediatric patients. Chest. 1998;114(4):1116-1121.

doi pubmed - Seldinger SI. Catheter replacement of the needle in percutaneous arteriography; a new technique. Acta Radiol. 1953;39(5):368-376.

doi pubmed - Laws D, Neville E, Duffy J. BTS guidelines for the insertion of a chest drain. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl 2):ii53-59.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization. Global Tuberculosis Control - WHO Report 2012. Geneva, Switzerland.

- Mandell LA, Wunderink RG, Anzueto A, Bartlett JG, Campbell GD, Dean NC, Dowell SF, et al. Infectious Diseases Society of America/American Thoracic Society consensus guidelines on the management of community-acquired pneumonia in adults. Clin Infect Dis. 2007;44(Suppl 2):S27-72.

doi pubmed - Yao CT, Wu JM, Liu CC, Wu MH, Chuang HY, Wang JN. Treatment of complicated parapneumonic pleural effusion with intrapleural streptokinase in children. Chest. 2004;125(2):566-571.

doi pubmed - Lombardi G, Zustovich F, Nicoletto MO, Donach M, Artioli G, Pastorelli D. Diagnosis and treatment of malignant pleural effusion: a systematic literature review and new approaches. Am J Clin Oncol. 2010;33(4):420-423.

doi pubmed - Luketich JD, Kiss M, Hershey J, Urso GK, Wilson J, Bookbinder M, Ginsberg R. Chest tube insertion: a prospective evaluation of pain management. Clin J Pain. 1998;14(2):152-154.

doi pubmed - Henry M, Arnold T, Harvey J. BTS guidelines for the management of spontaneous pneumothorax. Thorax. 2003;58(Suppl 2):ii39-52.

doi pubmed - Bediwy AS, Amer HG, Pigtail Catheter Use for Draining Pleural Effusions of Various Etiologies ISRN Pulmonology:10.5402/2012/143295.

- Jain S, Desokar RB, Barthwal MS, Rajan KE. Study of Pigtail Catheters for Tube Thoracostomy. MJAFI. 2006; 62:40-41.

doi

This is an open-access article distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Current Surgery is published by Elmer Press Inc.