| Journal of Current Surgery, ISSN 1927-1298 print, 1927-1301 online, Open Access |

| Article copyright, the authors; Journal compilation copyright, J Curr Surg and Elmer Press Inc |

| Journal website http://www.currentsurgery.org |

Original Article

Volume 7, Number 3, September 2017, pages 35-38

A Complete Clinical Audit to Assess the Compliance and Quality of the Safe Surgery Checks in OMFS Theater

Mohamed Haniaa, c, Amad Haniab

aOMFS, Leeds General Infirmary, Leeds, UK

bRoyal Victoria Eye and Ear Hospital, Adelaide Rd, Saint Kevin’s, Dublin 2, Ireland

cCorresponding Author: Mohamed Hania, OMFS, Leeds General Infirmary, 16 B Hartley Avenue, Leeds LS62LP, UK

Manuscript submitted June 17, 2017, accepted August 21, 2017

Short title: Closed Loop Clinical Audit

doi: https://doi.org/10.14740/jcs327w

| Abstract | ▴Top |

Background: The aim of the study was to assess the compliance and quality of safe surgery checks in the oral maxillofacial theater at Leeds General Infirmary.

Methods: This was an initial single blind prospective audit of 10 random surgical theater sessions using a safe surgery checklist toolkit table to assess the compliance and quality of the safe surgery checks. The results and recommendation of the initial audit were disseminated to staff at our monthly audit meeting, after which further random six theater sessions were re-audited.

Results: Initial audit showed a consistent result of compliance in all but two areas of safer surgery checks according to guidelines: 1) 100% compliance in sign-in, time-out, and sign-out taking place; 2) 100% of elements in surgery check covered and clearly announced with no interruptions; 3) 87.5% of team members “downed tools” for checks; and 4) 87.5% of team members were present for all stages of the checks. Re-audit showed satisfactory 100% compliance in all domains including areas that were shown to be suboptimal in the initial audit.

Conclusions: Further randomized auditing needed to maintain the compliance and improve any suboptimal results. We recommend further research be needed across a range of surgical departments in order to help strength the body of evidence behind the good standard and practice of safe surgery checklist.

Keywords: Safe surgery; Audit; Closed loop; Leeds; OMFS

| Introduction | ▴Top |

Over 234 million operations take place across the world annually [1]. This immense number of procedures will mean increased risk to patient and high likelihood of errors occurring in our high-volume, high-stressed hospitals. Therefore, avoidable operative complications can account for a high number of severe injuries and deaths in patients globally. It is estimated that rate of adverse events is at 3-16%, of which half were found to be preventable [2].

According to the National Reporting and Learning System, a central database set up by the National Patient Safety Agency under the auspice of the NHS, over 1.2 million safety incidents occurred in England and Wales in 2015 [3]. Over 75% of these incidents were in acute/general hospitals and a subset of 10% of these incidents was related to a treatment or a procedure [4].

In 2002, the World Health Assembly (WHA) adopted resolution WHA55.18 which requested the World Health Organization (WHO) to improve standards in efforts to minimize risk to patients undergoing any surgical procedure and assist in setting in place safety policies and practices. This led to the formation of alliance of experts which consisted of surgeons, anesthetists and patient safety experts to devote its time and energy to concentrate its actions on focused safety campaigns called “Global Patient Safety Challenges”. The first challenge setup was to deal and try to minimize the risk of cross-infection associated in healthcare, which led to the WHO’s first guidelines on Hand Hygiene in Health Care. The second challenge led to the preparation of the guidelines for safe surgery.

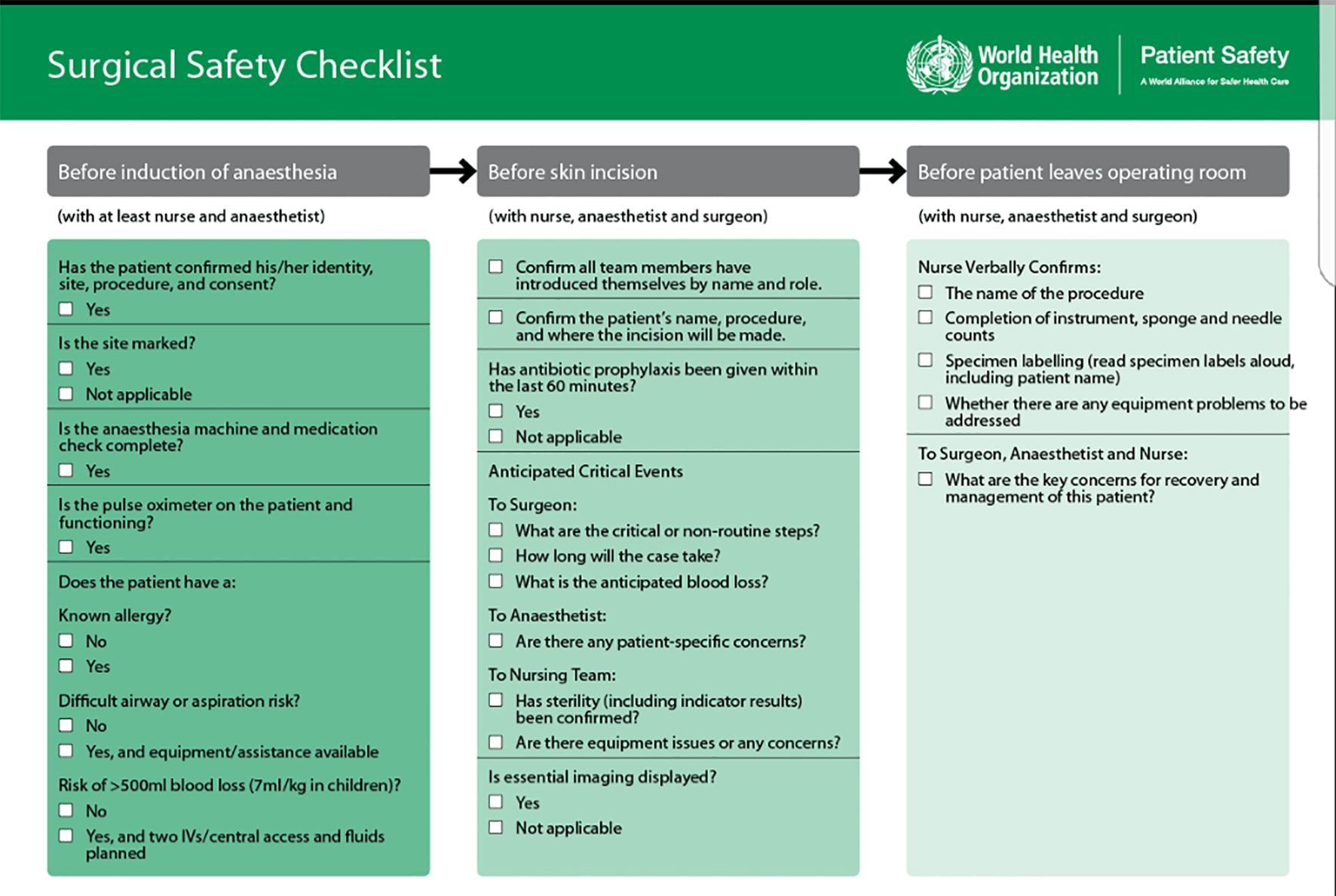

The guidelines consisted of a three-part checklist [5] (Fig. 1) before, during and after any surgical or operative procedure is completed on a patient.

Click for large image | Figure 1. Safe surgery checklist. |

Aims

The aims of this clinical audit were: 1) to assess whether the surgery check and briefing/debriefing were completed for every operative/surgical procedure in the oral maxillofacial theater; 2) to assess the quality of the surgery checks that was being completed as per specified guidelines; and 3) to analyze the collected data in order improve compliance and recommend any changes, if necessary.

Audit standards

The gold standard was 100% compliance in the completion of good quality safe surgery checks before every surgical/operative procedure.

| Materials and Methods | ▴Top |

A prospective audit was designed and performed from the dates October 10, 2016 to October 11, 2017.

Ten surgical theater lists were chosen at random during the course of full working week (Monday to Friday).

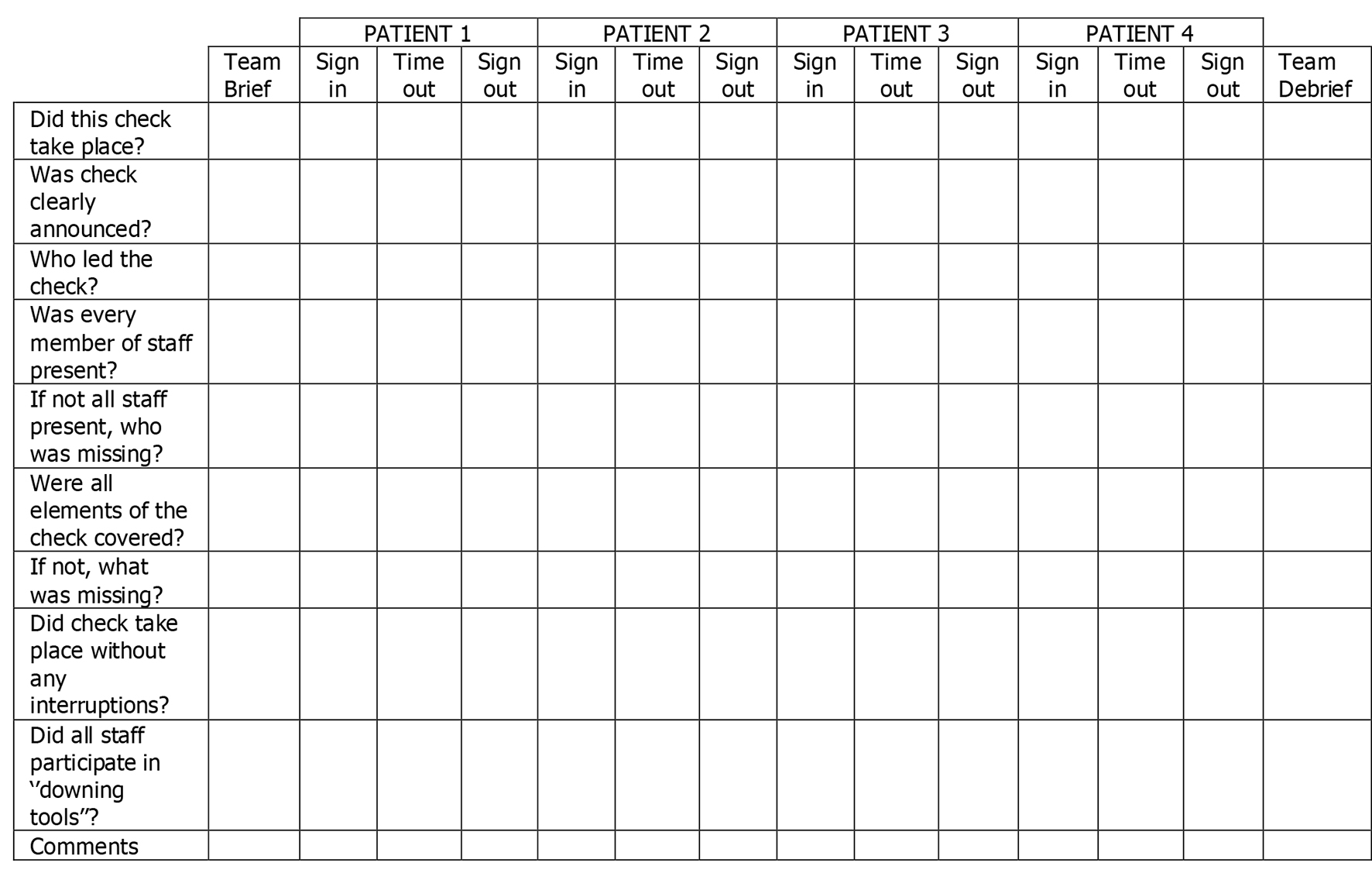

An audit table toolkit (Fig. 2) was utilized from the Leeds Teaching Hospital Trust clinical governance to assess the compliance quality of safe surgery checks per patient per theater session.

Click for large image | Figure 2. The safe surgery audit toolkit table. |

The only criterion in selection of a theater session was that a maximum of four patients must be operated on per list.

The audit was performed by the authors unbeknownst to the theater staff, surgeons or anesthetists.

After the initial audit, the results and recommendation were presented to our oral maxillofacial theater staff on our monthly audit meetings.

A subsequent re-audit of six theater sessions was undertaken prospectively as per above criteria.

| Results | ▴Top |

The data from the initial 10 clinical sessions audited were uploaded onto an excel spread sheet and analyzed. The results showed that 40 out of 40 patient safe surgery checks showed a sign-in, time-out and sign-out checks taking place resulting in a 100% compliance.

Of the 40 patient safe surgery checks carried out, all the elements included in the sign-in, time-out and sign-out checks were completed and clearly announced as heard by the author who was the furthermost staff at time of each check with no interruptions taking place while the checks were ongoing.

There was a 99.5% compliance in a single member of staff carrying out all stages of the safe surgery checks for all patients per theater list, which corresponds to a single time-out check being conducted by a different member of staff to the member who was responsible for all the safe surgery checks to be carried out on a particular theater list/session.

An 87.5% compliance was found with regards to the responsible members of staff, i.e. staff members who were present during the initial briefing were present during all stages of safe surgery checks. This corresponds to 25 safe surgery checks being missed by a member of staff during the course of the audit.

A similar 87.5% of staff were found to have “downed tools”, i.e. stopped any jobs they were doing and paid full attention to the safe surgery checks that were being conducted.

Recommendations

We recommended that further supplemental training and awareness regarding the benefits of well-conducted good quality surgery checks was to be disseminated to the clinical staff in the oral maxillofacial specialty via our monthly audit meetings and a re-audit to be conducted on unspecified dates.

We recommended that if a member of staff is to leave and not able to return to complete the remaining and/or any stage of safe surgery checks, that member must make it know to the remaining staff members and to arrange a replacement staff member to be introduced, if necessary.

We recommended that safe surgery checks be stopped and restarted if any member of the team was undertaking other tasks while the safe surgery checks were being conducted, i.e. did not “down tools”.

Re-audit of safe surgery

The data from further random six clinical sessions were uploaded onto an excel spread sheet and analyzed. The results showed that 24 out of 24 patient safe surgery checks showed sign-in, time-out and sign-out checks taking place resulting in a 100% compliance.

There was likewise 100% compliance in single member of staff completing all stages of safe surgery checks, like 100% of staff “downing tools” and being present through all stages while surgery checks were carried out.

| Discussion | ▴Top |

The WHO safe surgery checklist was divided into three stages: the period before induction, the period after induction but before any surgical incision, and the period after wound closure. It is recommended that a single member of staff (a checklist coordinator) be responsible for all safe surgery checks. There must be no proceeding to the next stage of the procedure until the checklist coordinator confirms completion of each stage of the check.

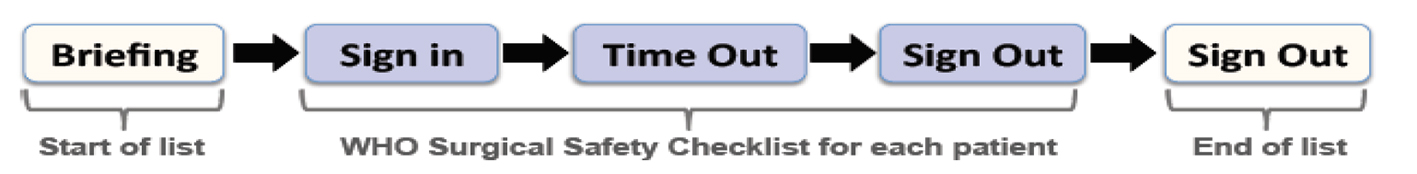

While initially the WHO guidance states a three-stage checklist must be completed, in England and Wales, the National Patient Safety Agency added an additional briefing and debriefing stage to the safe surgery checklist following its patient safety alert in 2009 [6].

This turned a three-stage checklist into a five-stage checklist (Fig. 3) and also resulted in a clinical lead from each organization to ensure that a checklist was completed for each patient and entered into the medical records of the patient.

Click for large image | Figure 3. Five stages of safe surgery. |

While the impact of the safe surgery checklist is difficult to know due to a lack of research following its implementation as a standard, it is important to note that the initial taskforce setup to come with the safe surgery guidelines investigated the effects of safe surgery checklist before and after implementation on in-hospital complications occurring within the first 30 days, and found that the overall death rate was reduced from 1.5% to 0.8% [7].

Furthermore, the presence of the above safe surgery checks was found to reduce level of stress and anxiety on a wake patient contrary to the hypothesis that it may add to added anxiety to the patients undergoing a surgical procedure.

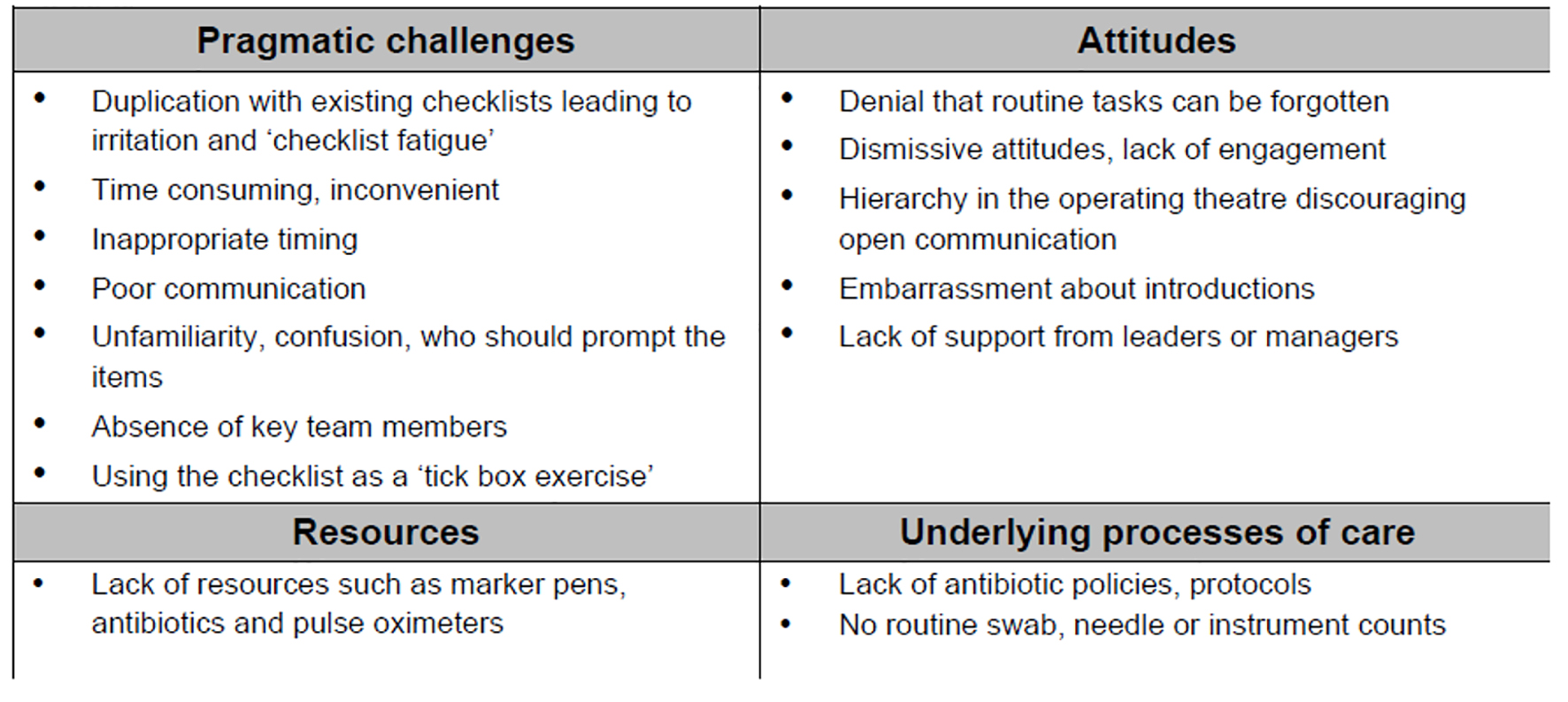

However, there are some barriers such as table below (Fig. 4) in the implementation and conducting of safe surgery checks as summarized excellently by Woodman et al [8].

Click for large image | Figure 4. Barriers to implementation of safe surgery checklist. |

Conclusion

While initially our compliance rate and safe surgery checks were satisfactory and met our initial gold standard of 100% compliance, the suboptimal performance in the same members of staff being present for all stages of checks and “downing of tools” was unsatisfactory.

We recommend that regular auditing as part of the overall clinical governance should aid in the maintenance and improvement of compliance in safe surgery checks across all surgical specialties.

We recommend research be needed across a range of surgical departments in order to help strength the body of evidence behind the good standard and practice of safe surgery checklist.

Acknowledgments

Authors would like to thank Manganesh Salker for his assistance in data collection and analysis, also to the Oral Maxillofacial Department at Leeds General Infirmary for their help and support during the course of this audit.

Conflict of Interest

The authors report no conflict of interest in this work.

| References | ▴Top |

- Weiser TG, Regenbogen SE, Thompson KD, Haynes AB, Lipsitz SR, Berry WR, Gawande AA. An estimation of the global volume of surgery: a modelling strategy based on available data. Lancet. 2008;372(9633):139-144.

doi - Kable AK, Gibberd RW, Spigelman AD. Adverse events in surgical patients in Australia. Int J Qual Health Care. 2002;14(4):269-276.

doi pubmed - National Reporting and Learning System. Nrlsnpsanhsuk. 2016. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=135611&type;=full&servicetype;=Attachment. Accessed April 22, 2017.

- National Reporting and Learning System. Nrlsnpsanhsuk. 2016. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/EasySiteWeb/getresource.axd?AssetID=135611&type;=full&servicetype;=Attachment. Accessed April 22, 2017.

- W.H.O Safe surgery saves lives. 2009. Available at: http://whqlibdoc.who.int/publications/2009/9789241598552_eng.pdf?ua=1. Accessed April 22, 2017.

- WHO Surgical Safety Checklist. Nrlsnpsanhsuk. 2009. Available at: http://www.nrls.npsa.nhs.uk/resources/?entryid45=59860. Accessed April 22, 2017.

- Haynes AB, Weiser TG, Berry WR, Lipsitz SR, Breizat AH, Dellinger EP, Herbosa T, et al. A surgical safety checklist to reduce morbidity and mortality in a global population. N Engl J Med. 2009;360(5):491-499.

doi pubmed - World Health Organization Surgical Safety Checklist. The Associate of Anesthetists of Great Britain and Ireland. 2016. Available at: https://www.aagbi.org/sites/default/files/325%20WHO%20Surgical%20Safety%20Checklist.pdf. Accessed April 22, 2017.

This article is distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution Non-Commercial 4.0 International License, which permits unrestricted non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited.

Journal of Current Surgery is published by Elmer Press Inc.